A few seismic events each year in Esterhazy area

August 11, 2025, 10:16 am

Ryan Kiedrowski, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

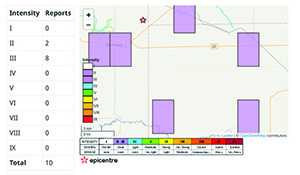

Allison Bent, a Research Seismologist from Earthquakes Canada, looked back 40 years in a 50 km radius of Esterhazy, finding that there are usually a couple seismic events every year.

“It suggests there are one to two a year,” she said of her research. “It’s not exactly the same number every year, but they’re almost all mining-related. I looked at a 50 km radius, they’re almost all in a much tighter area than that, very close to the mine. So, natural earthquakes are very rare, but as I said, small earthquakes can happen anywhere, but bigger ones tend to stick to the known seismically-active areas.”

Regions including Coastal British Columbia, the Atlantic, and St. Lawrence River are places where natural earthquakes are more frequent in Canada.

“In excess of 90 per cent of earthquakes worldwide occur at plate boundaries, so that’s the west coast of B.C. and the Yukon, they’re by far the most active areas in the country,” Bent said. “The bulk of what’s left over tends to occur at places that probably were at a plate boundary sometime in the distant past; so there’s still large areas of weakness. That will be the offshore east coast and along with St. Lawrence. There are small numbers that occur seemingly randomly, and it is the stresses from those distant plate boundaries that do trigger them, but because they’re so far away, they tend to be smaller and rare.”

Another clue that tells seismologists like Bent that the earthquake was likely caused by some sort of mining activities is the depth of where it happened.

“It depends where the earthquakes are,” she said when asked if there is such a determination of average depth when it comes to earthquakes. “They’re different in different places, but that was also one of our hints that it may have been induced or mining related—that it was so shallow. If it was deep, if it had been, say, 10 or 15 km, we would have said probably not, but natural earthquakes can be shallow.

“In eastern Canada, 15 km is about average,” Bent continued. “But there’s quite a range. They could be 25, 30 km or they might be 5 km. In the Maritimes, in the Appalachian area, they do tend to be a little bit shallower— maybe 5 km—and then in the subduction zones, where one plate is diving underneath another one, they can be much deeper, but it’s usually ‘kilometres plural,’ not less than one.”

Bent and her colleagues have been receiving an influx of messages since the Aug. 1 earthquake, something she attributes to the rarity of an occurrence in southeast Saskatchewan. “I think it’s why this has gotten a lot of attention, because they’re just less common,” she said. “In a place where you’re used to magnitude 5 and 6, a 3 is not that exciting! You notice it, you double check, ‘was it an earthquake?’ and that’s the end of it, whereas we notice in areas where they’re less common, they generate a lot more interest.”

There is no current method to predict when an earthquake will occur, but researchers like Bent have a general idea of where they can happen based on historical data.

“We know where they happen on the whole—we call it the largest probable earthquake rather than the largest possible—and how often they occur on average, but that really is an average,” Bent said. “We can’t tell you when the next one will be, and of course, that’s what people always want to know, so that’s why we work with the hazard maps and put provisions into the building codes, particularly in seismically active areas. We can’t tell you if it will happen tomorrow, but we can tell you the likelihood of it happening sometime during the life of a building.”

sm.jpg)